Built in 1912 for the princely sum of $60,000 (which would be well over $1 million in today’s dollars), Monmouth’s John Burrows Brown house is arguably the finest home built in the city during the early 20th century. Its history has been marked by both success and sadness.

Located at 700 East Broadway, the house’s history is closely tied to two of the oldest families in Warren County—the Eldridges and the Smiths. Truman Eldridge was a native of Massachusetts who came to Illinois in 1836, taking a claim on 240 acres near Roseville. Though his nearest neighbor was 12 miles away, he stuck it out, and eventually the village of Hat Grove was established, with part of his land being incorporated into the town. Hat Grove eventually changed its name to Roseville, and Eldridge served as its first postmaster.

Meanwhile, William F. Smith was opening Monmouth’s first general store in 1835. He later established Monmouth’s first drug store on the southwest corner of the Square. Smith, who served both as Monmouth postmaster and Warren County clerk, built a large, comfortable home stood on South Main Street, near the site of the current Maple City Restaurant. In 1838, he married Margaret Bell, daughter of the founding pastor of Monmouth’s Presbyterian Church. She bore him 10 children, including Edwin R. Smith, who entered his father’s drug business and in 1866 married Truman Eldridge’s daughter Irene. Irene gave birth to a daughter the following year, but sadly, Edwin died a year later, leaving her a widow with a baby daughter, Edna.

Irene returned to Roseville to live with her parents. In 1885, Edna enrolled at Knox College. There she met John Burrows Brown, a Connecticut native who came with his family to Rock Falls as a child. Upon graduation in 1886, Brown returned to Connecticut, where he worked as high school principal while studying law. He graduated from Columbia Law School in 1889 and returned to Illinois, where he was admitted to the bar and married Edna at Roseville. The couple moved to Minneapolis, where he practiced law for two years.

In 1891 the Browns returned to Roseville, and in 1897, John was appointed master in chancery for Warren County, holding that office until 1905. Brown then started a private law practice in Monmouth with his wife’s cousin, Glenn Soule. Soule’s father, Melville, had come to Monmouth in 1856 and enrolled at Monmouth College, where he met and married classmate Inez Bell Smith, the sister of Irene Eldridge Smith’s late husband.

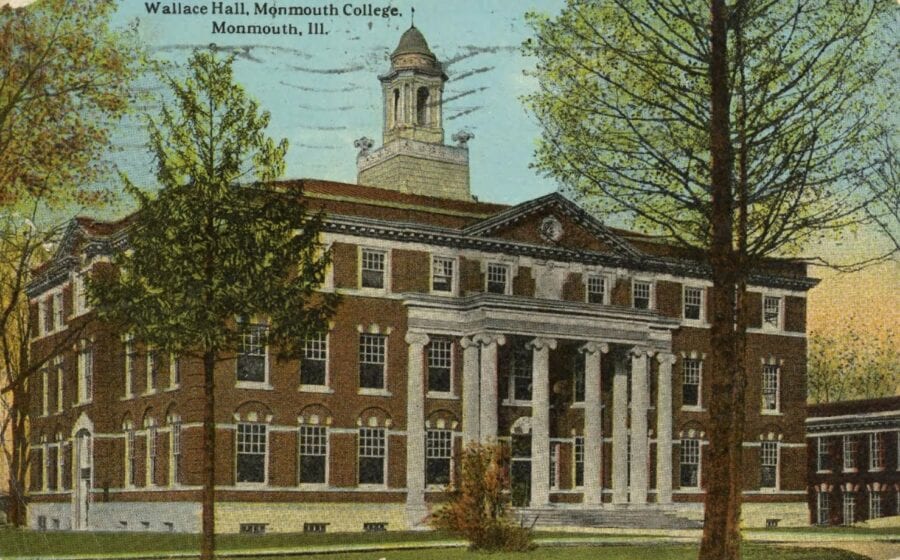

In 1911, the Browns the hired the prominent Peoria architectural firm of Herbert Hewitt & Frank Emerson to design their home. Hewitt had recently designed the new Wallace Hall at Monmouth College.

Built in the Tudor revival style, the Browns’ home featured a basement containing a 60-foot-long game room, laundry room, food storage pantry and wine cellar; five fireplaces, three full bathrooms and two half-baths; and a detached two-stall garage. A driveway from Broadway passed under a porte cochere on the east side of the house and led to a service court, from which a second driveway led to Sixth Street.

The main floor contained a central hall with stone fireplace and ornamental plaster ceiling. Flanking both sides of the hall were French doors leading to a reception room, a living room with elaborate casework, and a dining room with a built-in sideboard. Adjoining the dining room was a large breakfast room opening onto a side porch. A service wing, located north of the grand stairway, contained a modern built-in kitchen, a cold pantry, a servants’ hall and a telephone room.

At the top of stairs was a spacious upper hall surrounded by a master bedroom with a vaulted ceiling, a guest bedroom, and a bedroom for Brown’s mother-in-law, who moved with them from Roseville. That room featured a fireplace and a private balcony. There was also a spacious sitting room overlooking the front entrance, a sleeping porch tied to the master bedroom, and a family bathroom.

The Browns moved into their new home in 1913. They had three live-in servants—a chauffeur and two housekeepers. While the Browns were part of Monmouth society, they continued to play an active role in Roseville, particularly in the Congregational Church where they were members, and the Library Association, of which Edna was the first president.

John and Edna both suffered with ill health, and in they spent the summer of 1919 in Waukesha, Wisconsin, with Mrs. Smith and a niece, which proved beneficial to both of them. They were planning to go south for the winter, but in October, Edna contracted a severe cold. On Nov. 2, Edna died at the age of 52. Her funeral was held at the Brown home and she was buried in the family plot in Roseville Cemetery.

Brown continued to share the home with Edna’s mother, but by the next spring, his depression over his wife’s death and his own poor health were making him increasingly restless and nervous.

On the night of April 30, 1920, Brown dined with his mother-in-law and then retired to his room at 7:30. Mrs. Smith, thinking he intended to go to bed, remained downstairs. Shortly after 8, she heard a muffled report, but paid no attention. Two hours later, she retired to her own bedroom, next to Brown’s, and seeing a light under the door, looked in to see if he needed anything.

She discovered Brown’s lifeless body at the edge of his bed and between his feet was a .405 caliber rifle.

Mrs. Smith immediately called her nephew, Glenn Soule, who contacted the coroner. They and a neighbor met at the house and proceeded to the bedroom where they determined that Brown had taken a rifle from his closet, sat on the edge of his bed, and placed the gun between his feet with the barrel in his mouth. He had previously removed the shoe and sock from his right foot and he had tripped the hammer with one of his toes. The bullet went through his head and into the ceiling.

Brown’s funeral, held in the home the following Monday, was widely attended and burial was next to his wife in Roseville Cemetery.

Brown left the home to his law partner, Glenn Soule, with the provision that Mrs. Smith would continue to live there the rest of her life. Soule and his wife, Etha, moved into the house later that year.

Mrs. Smith survived nearly another decade—until 1929. In her will, she left the college $25,000 as a memorial to her father, who had been one of Monmouth College’s first trustees. In 1931, the college used the bequest as partial payment on the house, which it purchased for $35,000. Included in the sale were most of the home’s furnishings.

The college used the building to house its new Fine Arts Department, recently endowed by the prominent New York architect Dan Everett Waid, an 1887 MC graduate, in memory of his wife.

During World War II, the upstairs and it was converted to a dormitory for senior women, who had been displaced on campus by Naval preflight cadets.

In 1957, the college trustees saw a need to expand available space in Carnegie Library and authorized relocating administrative offices to a centralized location in the former Fine Arts Building. Today, the office of admission and financial aid occupies the building.

The John Burrows Brown house has had colorful array of tenants over the past century—two lawyers, the daughter of a pioneer, music faculty, college coeds, college presidents, deans and admission counselors. Recently renovated, it will likely remain a key Monmouth College property for decades to come.

For Maple City Memories, I’m Jeff Rankin.