DELIVERING ELECTION RESULTS TO THE MASSES—1912 STYLE

It was November 5—the night of the hotly contested presidential election—and hundreds of Monmouth residents were gathered around a big screen on South Main Street, intently watching returns as they were flashed from around the country.

Was it 2016 and were they in a local tavern? No—the year was 1912 and the crowd was standing on the sidewalk, facing what was then the E.B. Colwell Department Store, looking up at a giant piece of canvas stretched across the front of the building. Behind the onlookers, in the Daily Atlas building, reporters were feverishly watching the wires and working the phones to prepare slides for a stereopticon operator, who projected instant election results onto the screen.

Other Atlas staffers were manning two telephone hotlines, taking calls from subscribers throughout Warren County who wanted to know the results of local, state and national races.

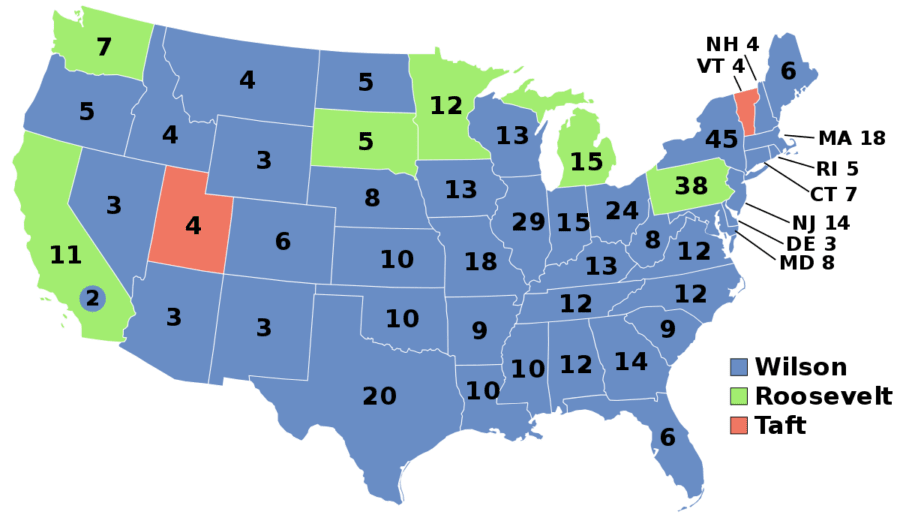

In the age before television and radio, there was no less eagerness among the public to quickly learn election results. The media was just as competitive as today and as eager to comply—particularly in a race as heated as that among Republican president William Howard Taft, Progressive challenger Theodore Roosevelt and the eventual victor, Democrat Woodrow Wilson.

From Philadelphia to Hartford to Brooklyn, newspapers adopted stereopticon technology to flash results of the 1912 contest. The Hartford Courant even employed a searchlight on its tower that pointed north for Republican victories and south for Democratic victories. The Brooklyn Eagle used combinations of red and white lights on its tower to communicate results. In Natchez, Miss., a newspaper boasted its results would be projected just 10 seconds after they came across the wire.

In Pittsburgh, a newspaper staff cartoonist drew clever one-minute sketches that were projected between election returns. A band played ragtime music and fireworks were also launched to announce results—for Wilson, shells exploding three times; for Roosevelt, showers of fire; for Taft spider-web shells. In an Olean, N.Y., movie theater, election results were flashed on the curtain between features.

The public ate it up. In Chanute, Kansas, crowds stood in the rain with umbrellas until 1 a.m., watching returns. There was an especially large contingent of women, due to equal suffrage measures on the ballot.

The technology was not without its dangers, however.

In Elgin, Ill., county judge Henry B. Willis was one of thousands of spectators standing in front of the Elgin Daily News watching returns projected on the building across the street. The Northwestern railroad tracks ran in front of the other building, and when a train approached, the crossing gate was lowered, isolating the judge between the gates and the train. Someone shouted a warning, causing him to turn, and at that moment the pilot beam of the engine struck him in the head and threw him beneath the wheels.

In Richmond, Ind., Miss Julia Thomas was watching election returns projected when two men started quarreling behind her. The discussion grew heated and one of the men hurled a brickbat at the other. The second man ducked and the projectile knocked Miss Thomas unconscious.

In an era before automobiles were common, one might assume that pulling election results off a wire and projecting them on a giant screen was an innovative technology, but that was far from the case:

- In the 1904 election won by Roosevelt, the Chicago Tribune rented nine large halls accommodating 31,000 persons to view stereopticon results, as well as projecting results for 15,000 persons on a giant screen at Clark and Sheffield.

- In the 1896 election between William McKinley and William Jennings Bryan, stereopticons projected results in Chicago, Buffalo, Brooklyn, New York City, Washington and Boston, to name just a few cities.

- In the 1888 contest between Benjamin Harrison and Grover Cleveland, a stereopticon projected results in St. Louis, where the crowd was so thick that a cab driver trying to negotiate his way through the street was pulled from his seat by the indignant election watchers.

One might wonder just how early the election stereopticon phenomenon was born. The stereopticon device was first introduced in 1850. A quarter of a century later, In the storied Tilden-Hayes race of 1876, the New York Herald projected returns at seven locations throughout the city, but that was still not the earliest use of the technology. The Indianapolis News of 1872 reported that the stereopticon method of displaying election returns was adopted in several cities that year—possibly due to the interest created by an intra-party split among Republicans, which led to celebrated newspaper publisher Horace Greeley representing both the Liberal Republicans and the Democrats against Republican president Ulysses Grant.

The stereopticon in its early days was powered by calcium lighting—also known as limelight—in which a mixture of oxygen and hydrogen gasses is directed at a cylinder of super-heated calcium oxide. The projector became popular theater fare, with images of exotic locations were thrown onto early movie screens. Dual lenses, by which the device derived “stereo” in its name, allowed one slide to seamlessly dissolve into the next. By the early 20th century, stereopticons were equipped with acetylene gas lighting and then carbon arc electric lighting, which is likely what the Atlas’s projector used.

The 1912 election was a particularly opportune time for stereopticon “coverage” to debut in Monmouth. That year’s ballot contained a dizzying 272 candidate names. Nineteen Monmouth men were on the ballot, including several candidates for state senate and house. There was also a referendum to amend the state constitution. And, for the first time in history, Monmouth women were allowed to vote—on their own special ballot, containing only the names of candidates for University of Illinois trustee.

In heavily-Republican Monmouth, it is no surprise that Woodrow Wilson did not fare as well as he did nationally. He won less than one-third of the popular vote, with Roosevelt capturing more than twice as many votes as Wilson. That had a disastrous effect on local elections, however, as a large percentage of Roosevelt voters marked only the Progressive party box of their ballots, ignoring all the local races, none of which had Progressive candidates.

For Maple City Memories, I’m Jeff Rankin.