Visionary pilot’s dreams dashed, but aviation took hold in Monmouth

On Thursday, Sept. 1, 1921, a large crowd was gathered at the baseball park on South 11th Street to watch a Twilight League contest between the local M. & St. L. and Professional teams. In the third inning, with the railroad boys leading 8–0, the crowd’s attention was drawn east to the sky over the Monmouth Country Club.

There, a Curtiss JN-4 “Canuck” biplane, flown by Lt. Arthur G. McMann of Davenport, Iowa, was preparing to land when suddenly its right wing bent upward and began to flop violently. The spectators, estimated in the thousands, were transfixed as they watched the experienced aviator try to right the aircraft. Flying at 5,000 feet, it appeared at first that he was succeeding, but when the damaged wing fell away, the nose turned downward and it became clear that a crash was inevitable.

With a sickening thud, the plane impacted the ground on the D.S. Hardin farm, a mile and a quarter east of town. First on the scene were three motorists — Wilmer Dew, Loxley Eckles and Charles Gawthrop (father of Monmouth’s future legendary pianist Gracie Peterson). They found the unconscious 28-year-old pilot still strapped in, clutching the control levers.

Within minutes, two physicians who had witnessed the crash — Dr. H.M. Camp and Dr. Ralph Graham — reached the wreck and saw McMann take his final breath. Camp examined McMann’s body and reported that his neck had been broken, his nose was crushed and he was covered with cuts and bruises. A large wooden splinter punctured his side and penetrated his abdomen.

The body was removed to the White & Lugg funeral home, where coroner John Lugg summoned a jury for the inquest. Meanwhile, thousands of townspeople visited the scene of the wreck before dark, where they were surprised to see the plane had not buried itself in the ground. The pilot’s pit was not damaged, but the engine had been driven through the front passenger seat. When souvenir hunters began dismantling the aircraft, a police officer was deployed as a guard.

Prior to his aviation ventures, McMann had run an automotive garage on Harrison Street in Davenport, but sold the business when he enlisted in World War I. He was sent to Kelly Field in Texas, where he learned to fly and was awarded a commission, but never flew in battle. After the war, he returned to Davenport and became an automobile dealer, with aviation as a sideline, but he eventually gave up the car business and established his own flying field on the west side of the city.

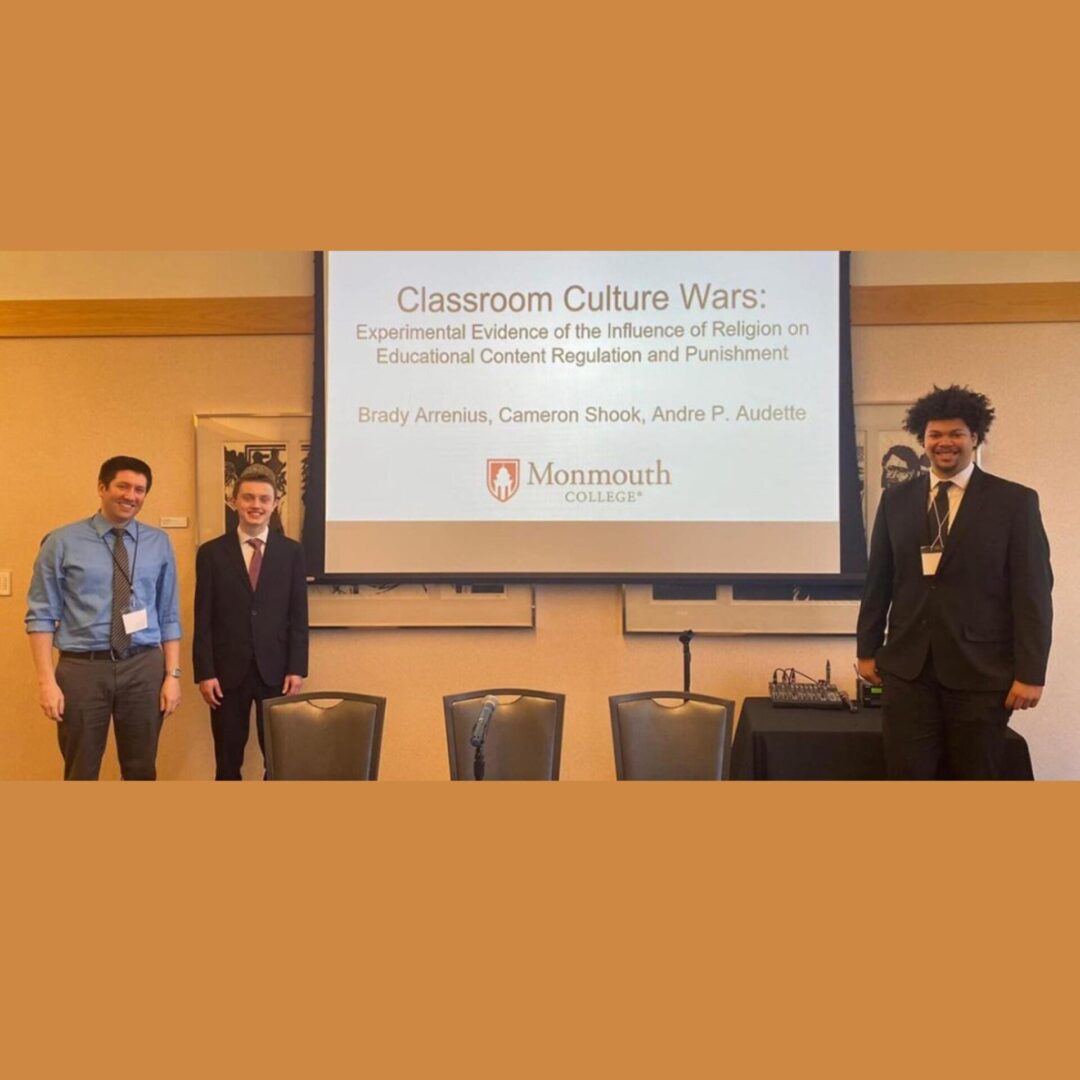

McMann had become quite a celebrity in Monmouth, where aviation was achieving widespread popularity and a movement was underway to establish a local flying field. (Founded shortly after his death, it is today is the longest continually operated airport in Illinois.)

In the spring of 1921, McMann he had come to Monmouth, where he began making good money flying townspeople in the Canuck’s passenger pit at $5 a ride. Among those shelling out the cash was 20-year-old Ralph B. Eckley, whose life was transformed by the experience, causing him to become one of Monmouth’s most avid pilots and aviation boosters until his death 68 years later.

McMann kept his plane on the Quinby farm on North Sixth Street, where he intended to erect buildings and open a flying school that fall, having already signed up a number of students. An advocate of careful flying, he had recently addressed a local men’s club, where he said that 90 percent of accidents were the result of carelessness and that he flew as little as possible over towns and cities. He also suggested that Monmouth pass an ordinance permitting no plane to fly lower than 1,500 feet over the city.

Before 1921, McMann declared he would never engage in stunt flying, which had become all the rage among barnstorming pilots. “All these stunt flyers get bumped off sooner or later,” he told the Davenport Times. “I’ll take straight flying for mine. Later however, he announced, “I’ll take a chance on getting knocked off.”

The weekend before the crash, McMann had performed a number of stunts that involved a wing walker, which some speculated had weakened the wing. It was also reported that he had had trouble with the motor and had recently installed a new cylinder.

Earlier that year, McMann was the guest of honor at a party in Chicago, where he met Miss Lois Viets, an art student. The couple fell in love and they were engaged to be married in October. They made plans for an aerial honeymoon in his plane, which he had named Lois — from Chicago to California, along the Pacific coast, across the American desert and over the Canadian Rockies. McMann promised Lois he would give up flying as soon as the honeymoon was over, and that he would be exceedingly careful in his flying work until the wedding.

Lois spent long hours on a painting of McMann’s plane and another of their future love nest cottage, which she planned to present to her future husband. Just as she was putting the finishing touches on the second painting, however, a telegram was delivered to the art school studio.

Other students heard a low groan and turned to see her faint and fall upon the easel, ripping the canvas. The telegram they found clutched in her hand read: “Arthur killed in 5,000-foot fall when Lois’ wing collapsed.”

For Maple City Memories, I’m Jeff Rankin.