Story Courtesy of Jeff Rankin, Monmouth College Historian Author and Literacy Critic.

When an arson fire damaged Monmouth’s Security Savings & Loan building on April 11, 1974, bank president Ralph Whiteman was probably relieved he was on an aircraft carrier in Oakland, California, performing exercises as a Navy Reserve officer. That’s because a week before the blaze he had joked with a fire inspector, “I guess the only way we’ll ever get out of this old building is if it burns down.”

Fortunately for Whiteman, he was never a suspect in the fire, which began at 2:30 a.m. Thursday in a pizza restaurant in the old Centennial Block, south of the bank, on the east side of the 100 block of South Main. Nine businesses were destroyed or damaged in the conflagration, including a magazine store, photography studio, an art studio, two barbershops and an insurance agency. In addition to the Centennial Block and the bank building, the Mayfred building on the Public Square would also be demolished.

Initially believed to have been set accidentally, the fire began in the kitchen of La Roma Pizza. John Hayes, a retired baker, had leased his former storefront to Sicilian pizza restaurateur Pete Vitale, who also owned a pizzeria in Fort Madison, Iowa. While Vitale returned for a visit to his native Sicily, he had left La Roma in charge of his 19-year-old Italian nephew, Vincenzo Pizzo, who had been working there for more than three years on a work visa.

Driven to the hospital emergency room by his girlfriend, a badly burned Pizzo initially claimed he closed up at 2:15 a.m. and then returned to make sure the back door was locked. That’s when he said an explosion occurred and he was burned fighting a grease fire.

Paul Brown, an employee of Admiral Co. in Galesburg, drove by the building on his way home from work and was first to phone in the fire. At about the same time, Lou Pavlic, proprietor of the nearby Italian Village restaurant was also closing up and started making coffee and sandwiches that would sustain the firefighters throughout the night. Mayor George Bersted, who was soon on the scene, asked Wilson Foods, Western Stoneware and Wells Pet Food to voluntarily suspend operations to conserve water for fighting the fire.

More than 5,000 gallons of water per minute were sprayed by a ladder truck and water cannons set on the pavement. The fire spread quickly to adjoining businesses, as crews frantically dug holes in South Main looking for the gas shutoffs.

When fire reached Newsland, a magazine store on the south corner which had just held its grand opening three days earlier, firefighters trained their nozzles on its upstairs windows, but were unable to break the glass. Italian Village employee Hank Stern ran back to the restaurant and returned with a case of beer. He and an associate bombarded the windows with beer cans, much to the consternation of thirsty onlookers.

Photographer Dick Wolfe watched helplessly as his collection of priceless negatives and unfilled orders went up in flames. He would end up purchasing a new camera later that day to fulfill a commitment to photograph a weekend wedding.

By morning, 20 downtown blocks had been closed to traffic, but onlookers crowded nearby businesses to observe the final efforts to douse the smoldering ruins. At 9 a.m., a crane from the Monmouth stone quarry appeared on the scene and began knocking down the century-old buildings with a massive wrecking ball. A fire wall stopped the flames from entering Security Savings and the Mayfred building, but they were so damaged by water and smoke that they would eventually have be razed. Optometrist Gary Distin and his wife, who lived above his shop on the Public Square, would also be displaced by the smoke damage.

Meanwhile, Register-Mail reporter Bill Campbell was interviewing Pizzo at Community Memorial Hospital. When Pizzo told him he believed the fire originated in the ceiling due to faulty wiring, Campbell reported the inconsistency to fire chief Swede Nelson and the state fire marshal. Officials also found it suspicious that on the morning of the fire, Pizzo had been scheduled to appear in Warren County circuit court on a charge of stealing $50 worth of hamburger from Giant Foods eight months earlier.

Pizzo checked himself out of the hospital on Saturday morning, asking hospital authorities not to inform the news media he had left. He was driven to Fort Madison, Iowa, to be nearer to family.

On Monday morning, after investigators found evidence of gasoline having been strewn on the premises of the restaurant, Pizzo was formally charged with arson and was apprehended by Fort Madison police, then released on 10 percent of a $10,000 bond. On April 25, a Warren County grand jury indicted Pizzo for arson. It then fell upon Warren County state’s attorney Fred Odendahl to ask Gov. Dan Walker to seek extradition from Iowa Gov. Robert Ray to return Pizzo for trial. Pizzo hired an attorney to fight extradition.

But Pizzo’s troubles weren’t limited to theft of meat and arson. In a few weeks he was scheduled to begin fulfilling mandatory military service in Italy. When Odendahl returned from filing the extradition papers in Springfield on May 1, he received bad news. The sheriff in Lee County, Iowa, had been told by Pizzo’s cousins that he had fled the country for Sicily.

The fire, with damages estimated at between $300,000 and $1 million, devastated the downtown business community. Basement barbers Hale McCurdy and Russell Strong had no insurance. McCurdy, who was recovering from a heart attack, was forced to retire and Strong lost a valuable collection of Warren County antiques. Shoe repairman Fred Larner’s basement shop was also destroyed. Commercial artist Royal Youngblood had minimal insurance and lost all his equipment.

Security Savings was more fortunate. The vault protected all of its important documents and within two days it had established temporary headquarters in the new AKT building at 318 North Main, using a borrowed computer. Within months, it would relocate, along with Peacock-Salaway Insurance, to a new building which was already under construction at 220 East Broadway. Newsland would relocate to South First Street, while Dick Wolfe would build a new studio on North Main.

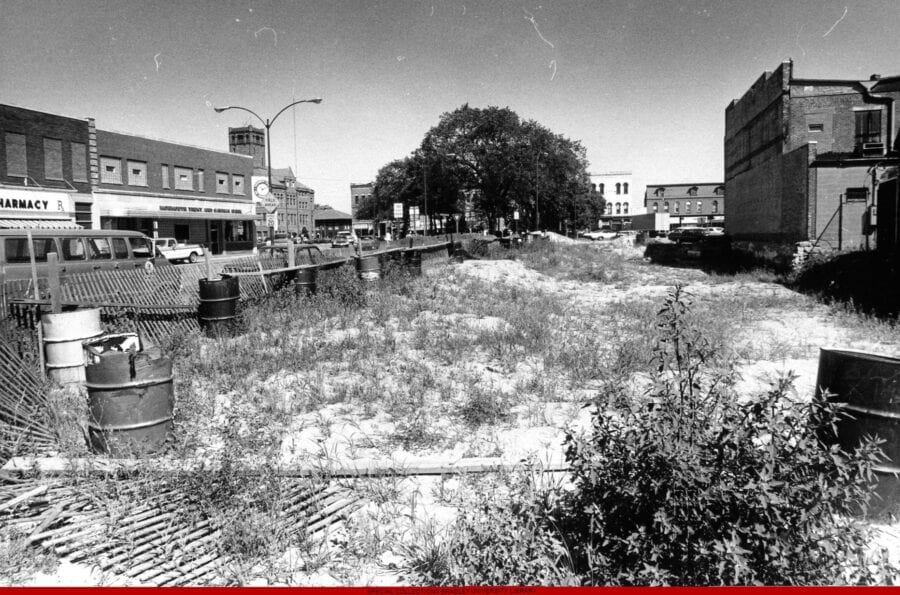

A year later, the entire block of the fire had become a city eyesore. Surrounded by a wooden snow fence, it had been filled with truckloads of sand and a humorist posted a “No Lifeguard on Duty” sign. The block had long been slated for urban renewal, with the hopes of attracting a shopping mall. But the buildings on the east side of the block were still occupied, and no investors would construct a new building on only half of a city block.

Eventually, Fred Odendahl built a law office on former Security Savings site, and the rest of the leveled block became a parking lot.

As was the case with a series of devastating Monmouth fires that were set in 1963, the 1974 arson case never went to trial.