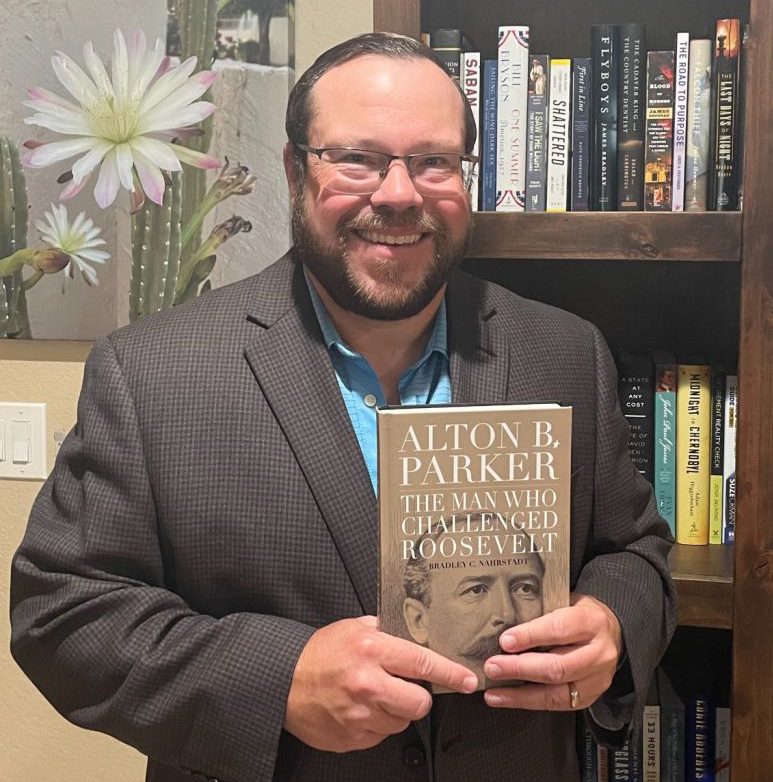

A member of the Monmouth College Board of Trustees has stepped up to fill a surprising void in the genre of American political biographies.

Brad Nahrstadt, a 1989 graduate of the College and a retired attorney, has written Alton B. Parker: The Man Who Challenged Roosevelt. Published by the State University of New York Press, the 357-page book is available in hardback, with a paperback version due out later this year.

‘That doesn’t seem right’

About 30 years ago, Nahrstadt’s interest in the judge-turned-politician was piqued when he discovered that Parker, one of the most important New Yorkers of the Gilded Age, was the lone member of an exclusive club.

Nahrstadt uncovered that vital nugget in Irving Stone’s classic book They Also Ran, which “provided a mini-biography of every man who’d run for president on a major party ticket and had not been elected,” he said.

In the 1904 presidential election, incumbent Republican Theodore Roosevelt routed Parker, a Democrat. Roosevelt captured more than 56% of the more than 12.7 million votes cast, winning the electoral vote 336 to 140. Parker won only 13 of the 45 states, all in what was once known in electoral politics as the Solid South.

“Stone wrote, ‘Of all the major-party candidates for president, Parker is the only one to never have a biography written about him,'” said Nahrstadt. “That just kind of struck me when I read it. I was like, ‘Well that doesn’t seem right, that he’s the only one – that no one has ever told his story.”

An avid collector of historical items – including an impressive collection of presidential campaign buttons spanning more than a century – Nahrstadt went to work correcting the historical oversight.

“Parker was a lawyer and a judge, and I was a practicing attorney, so I felt a kind of kinship with him,” said Nahrstadt. “I started collecting anything that I could find that I thought might shed some light on who Alton Parker was, what he did and about the campaign in 1904.”

The author or co-author of over 90 journal articles and more than 40 book chapters on legal issues, Nahrstadt eventually decided to take the plunge on Parker’s biography.

“I wasn’t 100% sure I was going to tell his story. Then I retired, and I had time on my hands. I thought, ‘Maybe I should roll up my sleeves and see if I can get this thing done.’ The reason I did it is I just didn’t think it was right that nobody knew about him and nobody had told his story.”

‘Too little, too late’

Parker’s omission from full biographies can be explained, in part, because of his short tenure in politics and the fact that he lost the election in what Nahrstadt called “spectacular fashion.” His 18.8% popular vote deficit was the largest in a presidential election since James Monroe essentially ran unopposed in 1820.

Prior to the election, Parker had worked his way up in law to “the one job he really wanted – chief judge of the New York Court of Appeals, which was, at the dawn of the 20th century, the second-most important court in the country,” said Nahrstadt. “It was his dream job. But Parker believed that in a democracy, if you were called, you had to answer the call. And so, when he was nominated to run in 1904, he quit the only job he really wanted to run against arguably one of the most popular people to ever be president.”

A doomed strategy sealed the landslide defeat. In 1896, Republican William McKinley had successfully run a so-called “front-porch campaign” against Democrat William Jennings Bryan from his Canton, Ohio, residence. Eight years later, that political ploy failed Parker.

“His problem was that people couldn’t get to his front porch (at a farm called Rosemount outside Esopus, New York),” said Nahrstadt. “There were people who were telling him, ‘Just stay at home. Run the campaign like McKinley. People will come see you.’ The problem was, Esopus, New York, is not close to anything. It’s an hour boat ride up the Hudson from New York City. It was a several-hour train ride. People just didn’t go because it was very, very difficult for folks to get there. His front-porch campaign just never materialized.”

Finally, with about a week left before the election, Parker got off his porch.

“He finally decided, ‘OK, I better get out and give some speeches,'” said Nahrstadt. “What’s funny is, he never went outside of New Jersey and New York (also Roosevelt’s home state). That didn’t help him. He should have gone to the Midwest. He should’ve tried to pick up Illinois, Indiana, Wisconsin, maybe Michigan. He just did too little, too late, and he lost in spectacular fashion. That’s really part of the reason why he was never written about. People just forgot about him.”

Finishing strong

No longer in the public eye after the 1904 presidential election, Parker finished his career successfully, even though he never returned to the bench.

“He was a very, very successful attorney in New York City,” said Nahrstadt. “He was president of the American Bar Association. He founded two different bar organizations in the state of New York. He was the personal attorney for (labor leader) Samuel Gompers and the AFL-CIO. He was the prosecuting attorney during the impeachment of the only New York governor (William Sulzer) to ever be impeached. So he did a lot of really, really important things. He just did most of them behind the scenes.”

While Parker went more than a century before an author penned his biography, the same cannot be said for his running mate in the 1904 election, Henry Davis, a millionaire and senator from West Virginia.

“There are actually two published biographies of Henry Gassaway Davis, but there weren’t any of Alton Parker, which I thought was very weird,” said Nahrstadt of the 81-year-old vice presidential candidate, an “astute businessman” with an “ungodly” amount of money. “Davis contributed very little in terms of effort. He gave a bunch of speeches, all in West Virginia, none of which, by the way, helped them carry the state.”

***Courtesy of Barry McNamara, Monmouth College***