Imagine you’re a sixth-grade student. Your father’s Navy commitment often takes him from home, but this time, you’re don’t know if he’s ever coming back.

Imagine the bittersweet emotions you experience several months later – at first, the euphoria that your father is, indeed, alive, but then the sobering fact that he’s a prisoner of war in North Vietnam. And, as it turned out, the most senior naval officer held captive by the North Vietnamese.

Now it’s a few years later, and there’s your mother on NBC’s Today morning show, being interviewed by Barbara Walters and Hugh Downs.

That’s what it was like to grow up Stockdale.

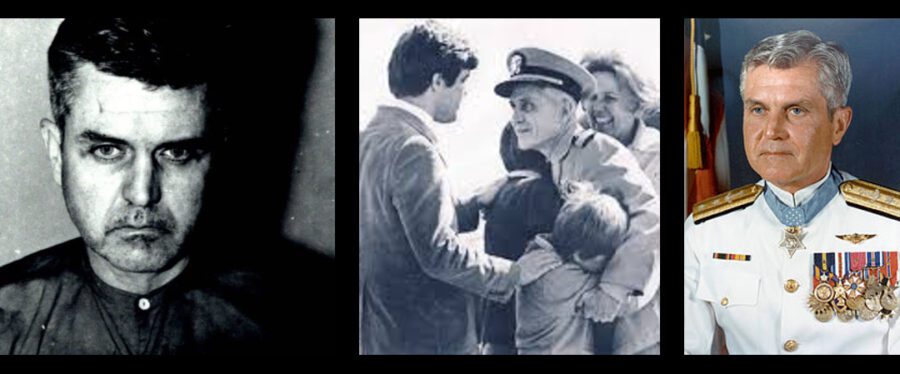

Sid Stockdale, author of a memoir titled A World Apart: Growing Up Stockdale During Vietnam, spoke Wednesday at Monmouth College, the school his father, Vice Adm. James Stockdale ’46, attended from nearby Abingdon, Illinois, before beginning his military service during World War II.

Two decades later, Stockdale was a fighter pilot – almost due to age out of the position – as tensions escalated in southeast Asia. Sid explained how his father and mother, Sybil, were right at the center of Vietnam War events – from his father’s involvement in early August 1964, to secretive correspondence between his parents, to his mother’s role as a leader in bringing attention to the plight of POWs.

‘The call to go had already been made’

Sid told how the now-infamous misunderstood incident in the Gulf of Tonkin on Aug. 2, 1964, provoked U.S. military on the scene, who were advised not to retaliate. But with that event fresh on that destroyer crew’s minds, sonar readings two days later seemed to indicate the presence of more enemy vessels.

“That evening, there was lightning on the periphery in both directions,” said Sid. “Dad flew to the area, but he told them, ‘There’s nothing out there,’ and he flew back to the USS Oriskany. As they determined later, the lightning was fooling the sonar operator. About 4 a.m., they woke Dad up and told him that Washington said to retaliate – to bomb North Vietnam.”

Stockdale was confused, as he knew there was nothing to the incident, and the destroyer captain shared a similar sentiment, telling Washington not to do anything.

“But the call to go had already been made by (Secretary of Defense) Robert McNamara and LBJ (President Lyndon Johnson),” said Sid. “That was the beginning of the war. … There’s a chapter in the book my parents wrote (In Love and War: The Story of a Family’s Ordeal and Sacrifice During the Vietnam Years) titled ‘Three Days in August.’ My dad ends that chapter saying, ‘That’s why that war was a bastard. It started out as one.'”

Sept. 9, 1965

Just over a year later, “We received word that my father’s plane was shot down over North Vietnam,” said Sid. “He was missing in action. His wingman saw his ‘chute deploy. You can imagine it was very, very life-altering for us. That was a tough go.”

Making it even tougher was that the Stockdale family – which also included Sid’s three brothers – had to suffer alone. There was no word – at least, not yet – from James Stockdale, and the family was told not to share their bad news with anyone due to what was known as “the keep-quiet policy.”

“The hardest thing was the not knowing and the keep-quiet policy,” said Sid. “But Mom was very stoic.”

And then, a few months later, there was a monumental shift. Two letters from Stockdale made their way to the family home in Coronado, California.

“For us, it was complete elation – he’s alive,” said Sid. “It was like a bolt of white light had come down, and all of a sudden, the world was a better place.”

Reading between the lines

What Sid didn’t know, but what his mother picked up on almost immediately, was the strange wording used by her husband in that first pair of three-page letters.

“Two days later, Mom left us to go to the Naval Intelligence Base, where she met with Cmdr. Bob Burroughs,” said Sid. “They flew her out to Washington, D.C., to talk about the letters.”

In his letters, Stockdale was using a code to describe his own situation – solitary confinement – as well as to identify other men who were prisoners of war.

“Getting that news out was important,” said Sid, “because throughout the war, the North Vietnamese never shared to the United States who they held prisoner.”

Soon, Sid’s mother was using her own code in letters to her husband.

“Burroughs helped devise a way for Mom to secretly communicate with Dad,” said Sid. “But there was risk involved. If it was discovered, the Vietnamese would view it as espionage – that Dad was a spy – and it would likely mean death. It was a pretty amazing scheme and a pretty daring scheme, if you ask me. It was always morphing. I didn’t know anything about it. Three guys in the Pentagon were the only ones who knew.”

At 41 years old when he was shot down and captured, Stockdale was on the upper limit of the age range for fighter pilots so, consequently, Sybil was one of the older wives of a POW. Through the National League of POW/MIA Families, which she founded, she became a leader in getting the word out about POWs – thanks, in part, to the suspension of the keep-quiet policy but also, said Sid, because “my parents were risk-takers. They didn’t hold back when they knew it was the right thing to do, despite the fallout they were going to get. That was the way they lived their lives.”

There is more, much more, to Sid Stockdale’s story, and it’s all in his book. That includes the role played by Ross Perot, who would, two decades later, name James Stockdale as his vice presidential running mate in his 1992 presidential bid. But after all the family had been through during the seven-year ordeal, it seems OK to flip ahead to the happy ending on Feb. 14, 1973, when the Stockdales were reunited.

“It was truly amazing to have him home,” said Sid. “It was unreal, is the best way to say it. It was an amazing, amazing time.”

In 1989, Monmouth College named its student center the Stockdale Center to honor the Congressional Medal of Honor recipient, and he was inducted into its Hall of Achievement in 2000. In 2016, the College established its James and Sybil Stockdale Fellows Program, a prestigious scholarship, leadership, service and enrichment program for Monmouth students.

In his remarks prior to Sid Stockdale’s talk, Monmouth President Clarence Wyatt shared that using Sybil’s name in the program’s title was intentional, paying tribute to her “extraordinary courage,” a trait she shared with her husband.

***Courtesy of Barry McNamara, Monmouth College***